The Persian Empire was one of the largest and richest kingdoms in ancient history, which had its center in what is now Iran. Around 1000 BCE, a group of nomadic peoples moved to the area, and from there it flourished. Architecture is the art of planning and constructing habitable spaces. This art form requires a great deal of time, effort, knowledge, equipment, supplies, and resources.

In the past, an area’s level of architectural skill was one of the most crucial factors in determining whether it could be classified as a civilization. Persian architecture is probably one of the most well-known ancient architectural styles and places in the world. Persian architecture reflects a rich culture that has evolved over 5 millennia of history, beginning with the earliest artifacts (ceramics and bronzes) from the 4th and 3rd millennia BC. Its roots can be found on the Iranian Plateau before the Persians arrived there when the first derived writing is thought to have appeared in the ancient city of Susa (Pottery civilization), according to some Sumerian sources.

Ancient Persian Art and Architecture(Achaemenid, Parthian and Sassanian)

Also Read: 26 Important Points About Khajuraho Temple in Madhya Pradesh, India

The Persians, who lived in a mountainous region and were influenced by a complex synthesis of Egyptian, Greek, and Mesopotamian art, developed a distinctive style that was both realistic and highly stylized, with decorative flattened spaces and ornamented surfaces. It is possible to describe Persian architecture as the ideal combination of simplicity and symmetry.

Persian architecture has a history of producing some of the most amazing and intricate works of art the world has ever seen due to its rich and varied past and different political and cultural variances.

Early influences for Persian art and architecture came from other ancient civilizations like Mesopotamia, Elam, and Susa. The art of Susa expanded by depicting dogs, the towering ziggurat, walls, and more modest structures that show attention to design and construction. Early Elamite artworks emphasized animal representations and the use of geometric and imaginative designs.

The Achaemenid Empire was established in around 550 BCE by the famous king Cyrus the Great ( 550-530 BCE), whose artistic creations drew inspiration from and improved upon earlier models. The ruins and artwork at Persepolis, the capital city designed and built by Darius I ( 522-486 BCE) and mainly finished by his son Xerxes I, are the best representation of Achaemenid art and architecture (486-465 BCE).

Mud brick had been used to construct earlier Elamite structures like Chogha Zanbil, but the Achaemenids worked mostly with stone and decorated it with elaborate bas-reliefs. Jewelry made by the Achaemenids was crafted from precious metals, frequently gold, and gems, and displayed an extraordinary level of artistry.

The Seleucid Empire (312–63 BCE) saw a decline in Persian artistic activity; however, the Parthian Empire (247 BCE–224 CE) saw a revival, and the Sassanian Empire (224-651 CE), whose empire drew from the extensive past of its forebears to produce some of the greatest monuments and works of art of the ancient world, saw the peak of the Persian art. The Persian artistic developments persisted in influencing Islamic art and architecture after the Sassanian Empire was conquered by Islamic Arabs in 651 CE, and many of these are now associated with the idea of Islamic art.

Early Architectural Works of Elam and Susa

Before the 3rd millennium BCE, nomadic and semi-nomadic peoples lived in the Susiana region for a few thousand years. Around 4395 BCE, they decided to settle and found the city of Susa. By 7200 BCE, the Elamites had already been installed in the area at Chogha Bonut. The tribes of the heights of the Zagros mountains and the Sumerians of Mesopotamia alternatively had an impact on these people’s existence on the Iranian Plateau.

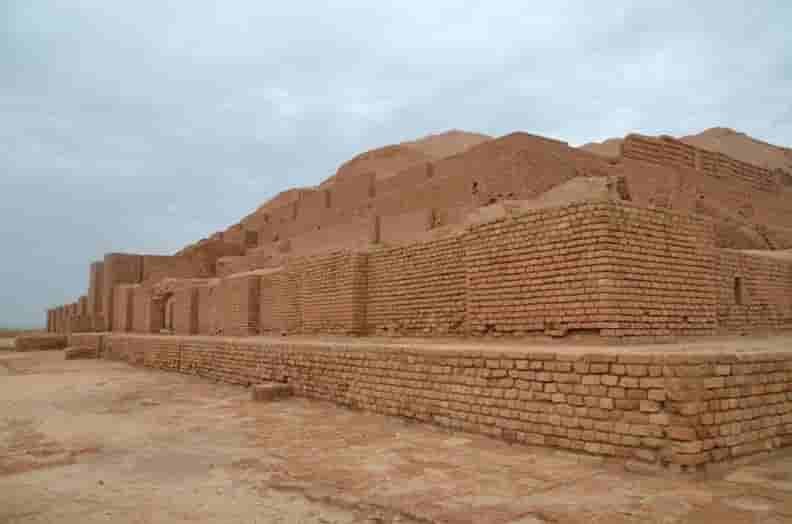

Under Sargon of Akkad’s rule ( 2334–2279 BCE), the Akkadian Empire expanded Mesopotamian motifs in local art. In terms of architecture, this influence was most pronounced in the enormous Chogha Zanbil building complex, which was constructed under Untash- Napirisha’s (1340 BCE). Chogha Zanbil was a wall and temples surrounding the Mesopotamian ziggurat. It was an effort to bring the many Elamite regions under the banner of Susa’s patron god, Inshushinak.

Chogha Zanbil used Mesopotamian motifs and construction techniques, even though it had an Elamite character and would eventually influence Persian art and architecture. The artwork of Elam before Chogha Zanbil, which depicts various deities and human figures in communal scenes is also clearly influenced by earlier Akkadian and Sumerian cylinder seals. These motifs would later be developed by the Persians.

Although the Persians had already arrived by the third millennium BCE, they had already made a permanent residence in Fars (Pars), a region near Elam that would later give them their name. To promote what is now known as Persian art and architecture, Cyrus the Great, who established the Achaemenid Empire in 550 BCE, drew on a rich tradition.

Achaemenid Architecture

The main concerns of Cyrus the Great and his son and successor, Cambyses II (r. 530–522 BCE), were the power consolidation and the expansion of the empire, although it is likely that they were also preoccupied with domestic issues. As a result, it wasn’t until Darius I’s reign that one finds any real attention paid to the advancement of art and architecture. Nevertheless, Cyrus spent a lot of time and thought on Pasargadae, his capital. Persian architecture included gardens heavily in its design and they were fundamental to it. Because these settings were so exquisitely created as to be nearly otherworldly, the Persian word for garden, pairi-daeza, is what gave English its word paradise.

It is reported that Cyrus spent as much time as he could in his gardens, probably to rest before dealing with concerns of the state. Large plots of flora and fauna were given a prominent place in the central courtyards of palaces and administrative buildings. The gardens were irrigated by the qanat system, sloping channels that brought water up from below the ground.

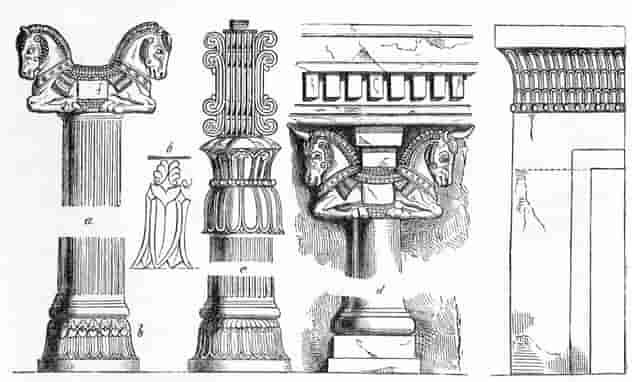

Darius, I reconstructed Susa and expanded the site with a palace complex, using Cyrus’ model of putting beautiful gardens at the center of the architecture. The Persian animal capital, which is a bull or a bird at the top of a column was invented by Darius I’s artisans for his buildings at Susa and Persepolis. These columns were also designed as slender pieces to draw the eye upwards to the capital figure while accentuating the grandeur of the height of the building.

Therefore, the columns were not merely standalone works of art but were also completely incorporated into the overall design of the building. The roof at Persepolis was built using a post-and-beam structure and was made of cedar from Lebanon’s forests.

Darius I also established the tradition of bas-relief ornamentation at Persepolis. The most well-known bas-relief at Persepolis depicts the many different Achaemenid Empire citizens arriving to pay homage to the Persian emperor. These images are so intricately detailed that the nationality of each person and the offerings they are shown bringing are clearly visible. The votive plaques in the Oxus collection and other examples, as well as the reliefs in Persepolis, all display attention to form and detail that animates the pictures and nearly gives them the appearance of Persepolis.

The Persian Architecture in the Parthian period

The Seleucid Empire, led by Seleucus I Nicator (305-281 BCE), one of Alexander the Great’s generals, was replaced by the Achaemenid Empire after it was overthrown by Alexander the Great in 330 BCE. Although the Seleucids preserved the earlier buildings, they naturally pursued their own artistic vision and produced works in their own manner because they were Greeks. When the Parthians conquered their empire in 247 BCE, Persian art and architecture once again began to advance. While the Seleucid Empire did see some progress, it did not experience it to the same extent as the preceding empire in terms of innovation and attention to detail.

Initially, the Parthians were semi-nomadic people, and their artwork reflects the various places they had encountered. Although they preserved the essential elements of Achaemenid art, their vision was represented in frontality and circularity in construction. The Achaemenids bas-reliefs were replaced by statues and images that look directly at the viewer. The frontal relief of a Parthian monarch offering sacrifice to the god Heracles-Verethragna, the protector god of royal dynasties, currently on display at the Louvre Museum, is a superb example of this.

For instance, the Romans had previously made extensive use of the dome; the Parthians simply developed this idea. Roman domes were built on top of buildings, while Parthian domes protruded from the ground. Parthian domes spotlighted height as well as strength and stability, drawing the viewer’s attention upward and then back down to the ground.

Sassanian Architecture

Ardashir I (224–240 CE), who ousted the final Parthian monarch and started his own dynasty had previously served as a general for the Parthians. The construction initiatives that still stand as outstanding examples of Sasanian art were almost immediately started by Ardashir I. The dome and minaret were introduced during the reign of Ardashir I and improved upon by his son and successor Shapur I (240–270 CE).

The Parthian and Roman dome and arch techniques were both used by the Sassanians to produce arch-supported structures that nonetheless communicated the idea of circularity. The best example of this is the famous palace at Ctesiphon known as Taq Kasra, which was most likely constructed by Kosrae I(531–579 CE) but is occasionally credited to Shapur I.

It has the longest single-span vaulted arch of unreinforced brickwork in the entire world, unmatched even now. As Ctesiphon was the Sassanian capital, the still-existing remains served as the entrance to a magnificent imperial palace that was designed to rival the grandeur of Achaemenid marvels like Persepolis.

Sassanian art preserved the floral motifs of the Achaemenids and the circularity of the Parthians, but it also added scenes of battle, religious motifs, and mythological stories, as well as depictions of the hunt, dances, parties, and other pastimes.

Iranian economist and historian Houma Katouzian asserts that, the rise of Islam in the seventh century CE and the Arab Muslim conquest of many areas that followed inevitably brought about the fall of the Sassanian Empire in 651 CE. Persian architectural styles persisted and eventually influenced Islamic and Arab buildings. The minaret, which is now almost universally associated with Islamic architecture, is a Sassanian invention.

Islamic Persian architecture

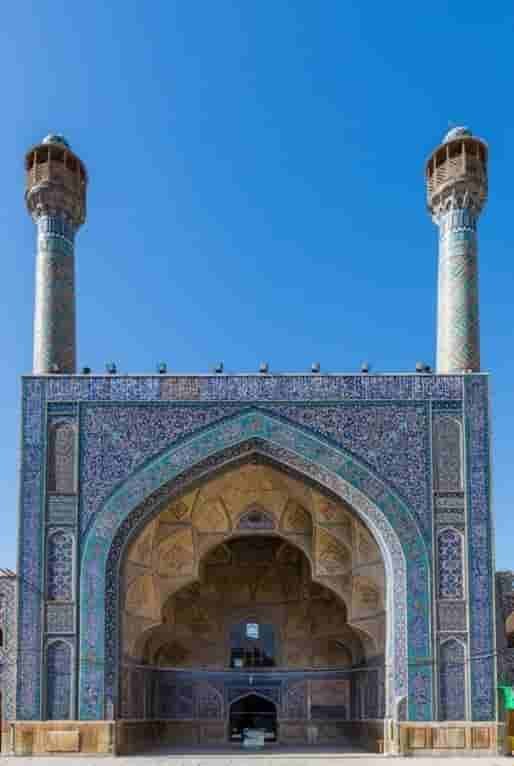

With the Islamic conquests in the 7th century, architecture developed a high level of refinement and a religious orientation. This style of architecture used colossal domes, muqarnas, and iwans, as found in Iranian mosques. The Persian Islamic style makes extensive use of delicate stucco work, mirrors, ceramic mosaics, stained-glass windows, and calligraphy as decorative features.

These components are ornamental, but they also serve as a divine sign. Pure geometric shapes like circles and squares are highly arranged in elaborate geometric patterns throughout Persian mosques. These beautiful shapes serve as a metaphor for the most amazing, by extension, for paradise and the divine.

Finally, the exquisite craft of pottery and tiling is an integral component of Persian architecture. It experienced a huge period of prosperity throughout the Islamic era and is heavily utilized in the embellishment of mosque domes as well as the vaulted ceilings of palaces and significant structures.

Conclusion

Ancient Persian architecture is considered one of the most amazing things that man has produced throughout history, because the development of this architecture was a reflection of the prosperity of the different periods that this region went through, from the beginning of the first periods of Elam and Susa through the Achaemenid period, then the Parthians and the Sassanians to the Islamic period. The impact of these periods on art, especially on architecture, was reflected in the forms of construction and decoration, and all of this had political, ideological, and many other implications.

According to American historian and archaeologist Arthur Pope, Iranian architecture has always been the summit of Iranian art in the truest sense of the word. The pre-and post-Islamic periods are both subject to the supremacy of architecture

Persian art and architecture continue to have a significant impact today. In order to preserve and honor the past, Persian architects and artists today draw on their history. Some artisans even continue to work with metals as their ancestors did thousands of years ago. One of the greatest of all ancient civilizations left behind some of the most famous ceramics, rugs, statues, and textiles in the world today.

Bibliography

- Arthur Upham Pope, Introducing Persian Architecture, Oxford University Press, London, 1971,p.1

- Bertman, S. Handbook to Life in Ancient Mesopotamia, Oxford University Press, USA, 2005.

- Blake, Stephen. Half the World, The Social Architecture of Safavid Isfahan, 1590–1722, Costa Mesa: Mazda, pp: 143–144

- Canby, Sheila R. (2009). Shah Abbas, The Remaking of Iran, p. 36.

- Harper, P. O, et. al, The Royal City of Susa: Ancient Near Eastern Treasures in the Louvre. Metropolitan Museum of Art, 1993.

- Hattstein, M. Delius, P. (2000). Islam, Art, and Architecture, Cologne: Köneman, pp. 513–514.

- Hejazi M., Historical Buildings of Iran: Their Architecture and Structure, Computational Mechanics Publications, Southampton,1997.

- Jayyusi, Salma K.; Holod, Renata; Petruccioli, Attilio; Raymond, Andre ,The City in the Islamic World, Volume 94/1 . 94/2, BRILL. pp: 173–176.

- Savory, Roger, Iran under the Safavids, New York, Cambridge University Press, p: 155, 1980.